But a deeper draw, I suspect, and a subtler one, lies in the Boxcar Children’s specific idea of a good time. When the first book was published, in 1924, Warner said that it raised a “storm of protest from librarians, who thought the children were having too good a time without any parental control!” She observed, in return, that this is exactly why kids liked the book. Work, especially: “The Boxcar Children,” one realizes upon rereading it, is an odd sort of capitalist parable, in which children without parents re-create the division of labor that, in the nineteen-forties, would become increasingly associated with a popular vision of the American nuclear family. But it’s that 1942 book that people remember, partly because it provides the children’s origin story, and partly because the appeal of the series can be traced to the beguiling tale that the first book tells, about work and family and life’s rewards.

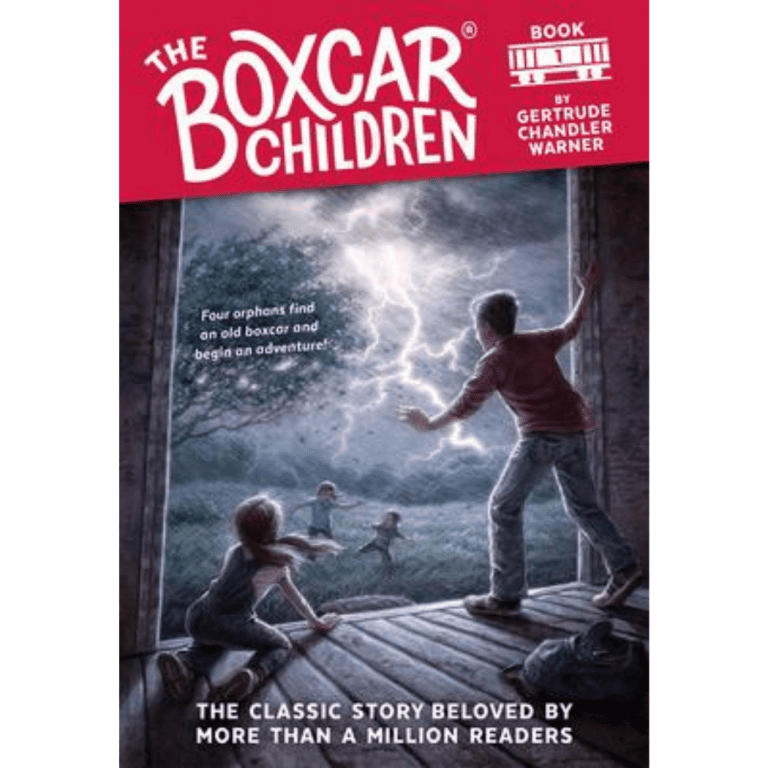

Warner wrote the first nineteen of those sequels, in which the Boxcar Children solve mysteries, herself all the rest have been ghostwritten. The book has never gone out of print, and it became the foundation for more than a hundred and fifty sequels, a dedicated museum in Connecticut, and, two years ago, an animated film. For the 1942 version, the story line and personalities of the main characters remained largely unchanged, but Warner abbreviated the text for younger readers, scrubbing it down to the simplicity of a fable-the vocabulary of the second edition was deliberately limited to six hundred words. The second time that Gertrude Chandler Warner published “The Boxcar Children,” a tale of four orphaned adventurers named Henry, Jessie, Violet, and Benny, the year was 1942, and the book was so successful that it erased Warner’s first version, published by Rand McNally in 1924 (with a hyphen in its title: “ The Box-Car Children”), from public memory.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)